When Haruki Murakami is discussed in literary circles today, it is usually for the elements that have become almost synonymous with his name: the lonely protagonists adrift in Tokyo, the vanishing women, the mysterious wells, the talking cats. Yet woven through nearly all of his major novels, from Norwegian Wood in 1987 through Kafka on the Shore in 2002 to the sprawling 1Q84 a decade later, runs another constant presence that deserves closer attention: Western classical music. And these are not casual references dropped in to create atmosphere. In Murakami’s hands, classical compositions become essential to how his stories are built, how his characters understand themselves, and how readers are meant to navigate the strange territories his fiction opens up.

Murakami came to writing through music, not the other way round. Between 1974 and 1981, before he had published a single novel, he ran a small jazz bar called Peter Cat in Tokyo, first in Kokubunji, then later in Sendagaya. The work was exhausting. When asked why he persisted with the gruelling schedule, Murakami gave a simple answer to The New York Times: “It enabled me to listen to jazz from morning to night”. Over those seven years, and in the decades since, Murakami assembled a record collection of some 10,000 albums. When conductor Seiji Ozawa, who would later become a close friend and collaborator, was asked about Murakami’s relationship with music, he said it went “way beyond the bounds of sanity”.

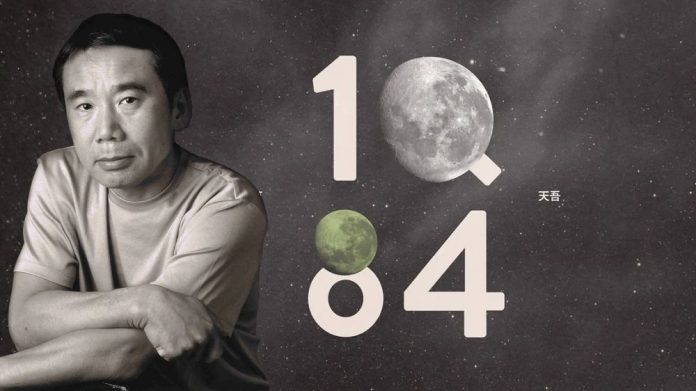

Janáček’s Sinfonietta and the Architecture of Alternate Realities in 1Q84

1Q84 opens with a moment of urban paralysis. Aomame, the novel’s protagonist, sits trapped in a taxi on Tokyo’s Metropolitan Expressway whilst Janáček’s Sinfonietta plays on the radio. The piece will return throughout the three volumes published between 2009 and 2010, recurring at moments when the narrative shifts between realities, when characters cross thresholds they cannot see. Janáček wrote the Sinfonietta in 1926, commissioned for a gymnastics festival organised by the Sokol movement. Sokol, meaning “falcon” in Czech, was founded in 1862 in the Czech territories of Austria-Hungary and promoted physical culture under the motto “a strong mind in a strong body”. Under Habsburg rule, Sokol functioned as a covert form of Czech nationalism. After the First World War and the establishment of Czechoslovakia in 1918, these expressions of national identity could emerge openly, and Janáček’s commission reflected that new freedom.

The Sinfonietta requires an unusually large brass section: twelve trumpets, four trombones, two bass trumpets. Its five movements carry programmatic titles referring to landmarks in Brno, Janáček’s city. The opening fanfare is bold to the point of aggression. Janáček described what he wanted to express: “contemporary free man, his spiritual beauty and joy, his strength, courage and determination to fight for victory”. One critic observed that this is “truly the worst possible music for a traffic jam: busy, upbeat, dramatic. Like five normal songs fighting for supremacy inside an empty paint can”. Murakami has said he chose the Sinfonietta precisely for that strangeness, for how ill-suited it is to the moment. The music does not fit the scene, and that wrongness alerts the reader that something has shifted, that Aomame is moving into a world that operates by different rules.

The architectural ambition of 1Q84 extends beyond the Sinfonietta. The first two volumes alternate between Aomame and Tengo across forty-eight chapters, a structure modelled on Bach’s The Well-Tempered Clavier, which contains forty-eight preludes and fugues in all major and minor keys. The third volume follows the pattern of Bach’s Goldberg Variations. Murakami constructed the novel as one might construct a piece of music, with formal patterns borrowed directly from the classical repertoire.

When 1Q84 was published in Japan, it sold more than one million copies within two months. The Sinfonietta sold approximately 6,000 CD copies in the first week, as many as it had sold in the previous twenty years. Seiji Ozawa reportedly thanked Murakami personally. Copies of Orwell’s 1984, the novel to which Murakami’s title alludes, also experienced a surge in sales. The readership followed Murakami into unfamiliar musical territory, seeking out a piece most had never heard before encountering it on the page.

Beethoven’s Archduke Trio and the Recognition of Moral Kinship in Kafka on the Shore

Kafka on the Shore, published in 2002, follows two seemingly unrelated narratives: fifteen-year-old Kafka Tamura fleeing his father’s house in Tokyo, and the elderly Nakata, who lost the ability to read and write after a childhood trauma but gained the inexplicable capacity to speak with cats. The novel is thick with musical references: Prince, Radiohead, The Beatles… But the classical works function differently, anchoring moments when characters grasp something about themselves they could not articulate otherwise. The most significant is Beethoven’s Piano Trio in B-flat Major, Op. 97, known as the Archduke Trio.

Beethoven composed the work in 1810 and completed it in March 1811. It was dedicated to Archduke Rudolf of Austria, the youngest son of Emperor Leopold II. Rudolf suffered from epilepsy, common amongst the Habsburgs, and his poor health meant he could not pursue a military career. Instead he entered the clergy and eventually became Archbishop of Olomouc in 1820. He began piano lessons with Beethoven in 1804 when he was sixteen, and was the only student to whom Beethoven taught composition. Rudolf proved talented and assembled an extensive music library, which he opened to Beethoven early in their relationship.

The premiere of the Archduke Trio in April 1814 was one of Beethoven’s final public performances as a pianist. His deafness had progressed to the point where his playing was painful to witness. The violinist Louis Spohr attended a rehearsal and later wrote: “on account of his deafness there was scarcely anything left of the virtuosity of the artist which had formerly been so greatly admired. In forte passages the poor deaf man pounded on the keys until the strings jangled, and in piano he played so softly that whole groups of notes were omitted”.

In Kafka on the Shore, Hoshino, a truck driver who has never paid attention to classical music, walks into a café and hears the Archduke Trio. The recording is the famous one by Arthur Rubinstein, Jascha Heifetz, and Emanuel Feuermann, sometimes called the Million Dollar Trio. The café owner explains why the piece carries that name: it was dedicated to Archduke Rudolf, who supported Beethoven throughout his life. Without Rudolf’s help, the owner says, Beethoven would have struggled far more than he did. Hoshino hears this and recognises something. He has been travelling with Nakata, helping the old man though he cannot fully explain why. The story of Beethoven and the Archduke gives him a way to understand what he is doing.

The relationship between Beethoven and Rudolf was complicated, but Rudolf’s financial support was unwavering. In 1809, when Beethoven considered leaving Vienna to become Kapellmeister at the court of Jérôme Bonaparte in Kassel, Rudolf joined with Princes Lobkowitz and Kinsky to offer Beethoven an annual salary if he stayed. When the other two patrons later faced financial difficulties or died, Rudolf continued the payments alone. Beethoven dedicated roughly fourteen works to him: the Fourth and Fifth Piano Concertos, the Piano Sonata Op. 81a (Les Adieux), the Violin Sonata Op. 96, the Piano Trio Op. 97, the Piano Sonatas Opp. 106 (Hammerklavier) and 111, the Missa Solemnis, and the Grosse Fuge.

Schubert’s Piano Sonata in D Major and the Philosophy of Imperfection

Elsewhere in Kafka on the Shore, the character Oshima, a transgender librarian who becomes Kafka’s guide and protector, plays Schubert’s Piano Sonata in D Major, D. 850, whilst driving. Schubert composed it in August 1825 in Bad Gastein, an Austrian spa town, which is why it is sometimes called the Gasteiner. Oshima tells Kafka that no pianist has ever played Schubert’s sonatas perfectly, and the reason is that the sonatas themselves are imperfect.

Robert Schumann coined the phrase “heavenly length” to describe Schubert’s Great C major Symphony, D. 944, though the term has since been applied to the late piano sonatas as well. For the D Major Sonata specifically, Schumann used the phrase “Heavenly Tedious,” acknowledging both its beauty and its sprawling, pastoral scale. Schubert’s late sonatas are unusually long; the first movements alone, with exposition repeats observed, can last as long as an entire Beethoven sonata. This creates difficulties for performers in terms of physical stamina and maintaining a coherent sense of the cyclic motifs that recur throughout.

Oshima explains to Kafka what he finds in this music: “A dense, artistic imperfection stimulates your consciousness, keeps you alert… listening to the D major, I can feel the limits of what humans are capable of. That a certain type of perfection can only be realised through a limitless accumulation of the imperfect”. The novel returns repeatedly to this idea. Characters are incomplete, their understanding partial, their losses irrecoverable.

The sonata is written in four movements. The first, Allegro vivace, opens with a fanfare that is immediately repeated in the minor and then developed in ways characteristic of Schubert’s compositional method. The second subject has been compared to Austrian yodelling and shares melodic similarities with Schubert’s setting of Johann Ladislaus Pyrker’s Das Heimweh (Homesickness). The sonata was composed at the same resort that inspired that song, creating connections between Schubert’s vocal and instrumental work. The harmonies appear deceptively simple, the textures easy, but beneath that surface lies considerable structural sophistication. Performers have described the sonata as offering “a warmly feeling inside,” a contrast to the turbulent drama of much Romantic piano repertoire.

The Broader Classical Repertoire and Murakami’s Aesthetic Project

The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle, published in Japan between 1994 and 1995, opens with Toru Okada in his kitchen, cooking spaghetti and whistling along to Rossini’s overture to La gazza ladra (The Thieving Magpie). “When the phone rang I was in the kitchen, boiling a potful of spaghetti and whistling along with an FM broadcast of the overture to Rossini’s The Thieving Magpie, which has to be the perfect music for cooking pasta,” Murakami writes. The overture is light, buoyant, almost absurdly cheerful. What follows in the novel is anything but: Okada’s wife disappears, he descends into a dry well, and the narrative spirals into wartime Manchuria and acts of unspeakable violence. The irony is deliberate. The music sets up an expectation that the novel immediately subverts.

Norwegian Wood, published in 1987, became Murakami’s most commercially successful novel and remains his least surreal. The protagonist listens to Miles Davis’s Kind of Blue, and the title comes from The Beatles, but classical references still appear, albeit less frequently than in later work. More significant is the recurring presence of Liszt’s Le mal du pays from Années de pèlerinage across multiple novels. The piece (its title translates as “homesickness”) appears again in Colorless Tsukuru Tazaki and His Years of Pilgrimage (2013), where it becomes structurally central. The novel’s title directly references Liszt’s three-volume collection of piano works documenting his travels through Europe. The character Haida explains Le mal du pays as “a groundless sadness called forth in a person’s heart by a pastoral landscape”. Tsukuru Tazaki, the protagonist, returns to the piece repeatedly, listening to it as he tries to understand losses he cannot name.

Murakami’s engagement with classical music deepened through his friendship with Seiji Ozawa. In 2011, they published Absolutely on Music, a transcription of six conversations interspersed with shorter “interludes” during which they listened to recordings from Murakami’s collection. Ozawa, as mentioned earlier, described Murakami’s devotion to music as going “way beyond the bounds of sanity”. One reviewer noted that “though it is Ozawa’s history, the book ultimately belongs to Murakami. The comparison to Glenn Gould is an apt one, I feel, for Murakami’s prosody is, like Gould’s musical syntax, both engaging and strongly idiosyncratic. The language is unmistakably Murakami’s throughout”.

Classical music in Murakami’s novels functions as more than reference or atmosphere. Through careful selection of works by Janáček, Beethoven, Schubert, Bach, and others, Murakami builds narratives that carry the formal complexity and emotional resonance of the music itself. The Sinfonietta structures the alternate realities of 1Q84. The Archduke Trio allows Hoshino to recognise moral kinship in Kafka on the Shore. Schubert’s D Major Sonata articulates a philosophy of imperfection that runs through the entire novel. Murakami’s fiction demonstrates that novels can function as sonic artefacts as much as literary ones, that music and prose together can reach places neither could reach alone. His work invites readers to hear what they read, to follow the music into unfamiliar territory, to understand that structure and emotion are inseparable from sound.