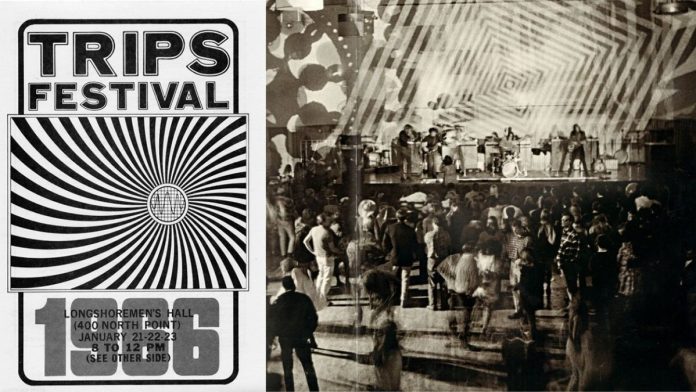

The Trips Festival did not announce itself with fanfare or advertisement spreads in glossy magazines. It arrived at the Longshoreman’s Hall in San Francisco during the weekend of 21 to 23 January 1966 as something the city’s establishment could not quite name, could not quite control, and certainly did not expect. Within seventy-two hours, more than six thousand people had passed through its doors, stumbling through corridors bathed in fractured light, encountering music that seemed to come from everywhere at once, and walking into a future that Ken Kesey, Stewart Brand, and the Merry Pranksters had effectively chosen for them. What happened that weekend remains one of the most significant confluences of art, music, and social upheaval in American cultural history, yet it emerged not from careful planning but from the collision of disparate energies that had been building independently across the Bay Area since late 1965.

To understand the Trips Festival is to understand the particular moment it seized. The psychedelic drug LSD remained legal in California, a fact that would not change until Governor Ronald Reagan signed legislation making it illegal on 6 October 1966, nine months after the festival. Ken Kesey, already famous for his novels One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest and Sometimes a Great Notion, had become consumed with the possibilities of LSD after volunteering for Project MKUltra, the CIA’s classified programme investigating hallucinogenic drugs. Beginning in November 1965 with a party at Ken Babbs’ house in Soquel, California, Kesey and his circle of friends – the Merry Pranksters – began hosting Acid Tests, gatherings that combined LSD distribution with music, psychedelic light shows, and the kind of improvisational theatre that belonged neither to traditional performance art nor to rock concert tradition. These events took place at Kesey’s home in La Honda and gradually moved into public spaces. The Grateful Dead, then a relatively unknown group barely distinguishable from countless other Bay Area ensembles, became the house band for these experiments.

Stewart Brand inhabited a different sphere. Trained as a biologist and fascinated by systems thinking and American space exploration, Brand had spent the mid-1960s contemplating why NASA had never photographed the whole Earth from space. His obsession materialised into buttons bearing the question “Why haven’t we seen a photograph of the whole Earth yet?” – buttons he sold whilst driving across America to raise awareness. This same analytical mind that would eventually conceive of the Whole Earth Catalog discovered in Kesey’s Acid Tests something worth organising on a grander scale. Brand recognised that what Kesey had developed in miniature could be expanded, made public, transformed into what he termed “a new medium of communication and entertainment.”

The third major figure, Ramon Sender, came from the avant-garde musical establishment. A composer and co-founder of the San Francisco Tape Music Center, Sender brought an understanding of electronic music, tape composition, and visual art that lent sophistication to what might otherwise have remained a chaotic drug party. Where Kesey represented the literary counterculture and Brand the visionary technologist, Sender represented the legitimate experimental music world. His participation legitimised the Trips Festival not in establishment terms but in the eyes of serious artists who otherwise might have dismissed it.

Bill Graham, who would eventually become one of rock music’s most powerful promoters, entered the picture almost accidentally. Graham had been managing the San Francisco Mime Troupe, a politically engaged theatre company, and was organising a series of benefit concerts to raise money for legal fees the group incurred through frequent run-ins with authorities. When asked to help organise the Trips Festival, Graham arrived with a clipboard, a sense of business protocol, and absolutely no understanding of what he was walking into. The weekend would reshape his career entirely.

The Machinery Behind the Spectacle

The Longshoreman’s Hall, an odd-shaped building constructed in 1959 at considerable expense, sat at 400 North Point Street. Oddly, despite its name, the hall was never actually used by the Longshoreman’s Union itself – that confusion belonged to the Maritime Hall, home of the rival Sailors Union. The building’s accessibility derived partly from the fact that many Hells Angels held membership in the Longshoreman’s Union, a peculiar detail that would become relevant when violence nearly erupted during the second night of the festival.

The technical infrastructure speaks volumes about what the Trips Festival actually attempted. Ken Babbs, a Merry Prankster and veteran sound engineer, worked with Don Buchla, the electronic music pioneer who had been developing what would become known as the Buchla Box, one of the first synthesisers. He arranged ten speakers around the balcony of the hall in a configuration that allowed sound to be manipulated, routed around the space in circles, isolated, and recombined in ways that had never been attempted in a concert setting before. The Buchla Box itself could be played like a keyboard, its flat surface allowing performers to create sounds through their fingers, and Babbs used it as an instrument capable of altering the very texture of what the audience heard. This was not a rock show with amplified guitars and drums; this was an attempt to create what the Grateful Dead’s bassist Phil Lesh would later describe as an “ebb and flow between the band and the audience,” a dissolution of the boundary separating performer from listener.

Equally important was the visual component. Owsley Stanley, the LSD chemist whose supply fuelled the Acid Tests, also ran the sound system and oversaw the lighting design. Liquid light shows, a term that itself barely existed before 1966, bathed the hall in fractured, moving patterns. Five movie projectors displayed films whilst light machines projected interferometric patterns, what one observer described as “intergalactic science-fiction seas all over the walls.” Black lights activated fluorescent paint. Strobe lights created temporal disorientation. Street lights at every entrance flashed red and yellow. Various artists and performers, including members of experimental theatre collectives, contributed to the visual spectacle. The San Francisco Mime Troupe performed provocative skits. The San Francisco Tape Music Center presented electronic compositions. The boundary between audience and performer essentially vanished.

Stewart Brand brought his own contribution: a multimedia presentation combining taped music with slides of Indian life and various visual elements that had debuted at earlier Acid Tests and reached full expression at the Trips Festival.

The Performances and the Chaos

The festival’s advertisement promised “a JUBILANT occasion where the audience PARTICIPATES because it’s more fun to do so than not.” That phrasing, almost accidental in its prescience, captured something essential about what made the Trips Festival different from every rock concert that preceded it. The bands did not perform to an audience; the audience collectively performed by being present, ingesting LSD-spiked punch, dancing, wandering, encountering theatre, film, music, and visual art in sequences that had no predetermined order.

The Grateful Dead played the festival just weeks after playing their first major San Francisco performance on 8 January 1966 at the Fillmore Auditorium as part of an earlier Acid Test. At the Trips Festival, the Dead represented the emerging sound of the Bay Area: hypnotic, improvisational music that moved far beyond the three-minute singles format dominating radio. Jerry Garcia’s guitar playing created what later observers would describe as a spongy, malleable texture perfectly suited to the psychedelic experience. Yet Garcia arrived at the festival with a damaged instrument; his guitar had been broken, creating circumstances that would necessitate Bill Graham’s famous gesture of attempting to tape the guitar back together during the second night so the Dead could perform. They never did manage to play that evening, but the image – Graham frantically trying to reassemble an instrument whilst the chaos of the festival swirled around him – became emblematic of the collision between old-style concert promotion and the new sensibility emerging at the Trips Festival.

Big Brother and the Holding Company, at this point an instrumental ensemble functioning as a house band for jam sessions in the basement of a Victorian house on Page Street in the Haight-Ashbury neighbourhood, made their official debut at the Trips Festival. These musicians had not yet encountered Janis Joplin, who would not join the group until June 1966 at the Avalon Ballroom. Yet their performance at the Trips Festival established them as part of the San Francisco scene’s developing mythology. They would, within months, become inseparable from Joplin’s arrival and her meteoric rise to prominence following her appearance at the Monterey Pop Festival in June 1967.

Jefferson Airplane, already the subject of national attention following their recording contract with RCA Victor signed in November 1965 for the then-extraordinary sum of $25,000, performed at the festival. The band had moved from folk-inflected arrangements to the more electric, psychedelic sound that would define the San Francisco scene. Grace Slick, Jorma Kaukonen, Paul Kantner, Jack Casady, and the rhythm section had begun to coalesce into the configuration that would record Surrealistic Pillow in Los Angeles just weeks after the festival, the album that transformed them from a local phenomenon into an international presence.

Yet the performances themselves occupied only one portion of the seventy-two-hour experience. Tom Wolfe’s account in The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test, published two years after the festival, captured the visual chaos with precision: “Lights and movies sweeping around the hall; five movie projectors going and God knows how many light machines, interferrometrics, the intergalactic science-fiction seas all over the walls, loudspeakers studding the hall all the way around like flaming chandeliers, strobes exploding, black lights with Day-Glo objects under them and Day-Glo paint to play with, street lights at every entrance flashing red and yellow, two bands, the Grateful Dead and Big Brother & the Holding Company and a troop of weird girls in leotards leaping around the edges blowing dog whistles.”

The second night, Saturday 22 January, descended into violence and confusion. Hells Angels members, some of whom were sympathetic to the Pranksters, others viewing the event as an invasion of their territory, began fighting members of rival motorcycle clubs in the hallways. The Pranksters, in their anarchic way, attempted to prevent Big Brother and the Holding Company from stopping their set at one point. Ken Kesey, legally forbidden from the hall due to his pending marijuana charges, attended in disguise wearing a silver space suit with helmet and addressed the crowd over the public address system from the balcony. When Bill Graham frantically searched the hall with his clipboard trying to locate Kesey and stop him from letting in people for free, he found the novelist in the space suit at the back door, admitting Hells Angels and various hangers-on without regard to admission. Kesey simply lowered his visor and ignored Graham, who began screaming at him. Bob Weir of the Grateful Dead, witnessing this confrontation between Graham and the Pranksters, turned to his companions and asked, “Who’s that asshole with the clipboard?” Graham’s entire career in rock promotion arguably began in that moment of mutual incomprehension.

Aftermath

The Trips Festival grossed $12,500, an extraordinarily profitable figure for an event that held almost no overhead costs and charged admission at approximately what a rock concert might otherwise charge. The financial success alone surprised everyone involved, including Graham, who suddenly understood that there existed a market for these experiences, that people would pay to enter what was essentially a drug party disguised as artistic expression. More profoundly, the festival demonstrated to thousands of attendees that they were not isolated anomalies but part of a genuine movement.

Tom Wolfe’s summary, published years after the fact, captured the historical significance: “For the acid heads themselves, the Trips Festival was like the first national convention of an underground movement. The heads were amazed at how big their ranks had become… The Haight-Ashbury era began that weekend.” Kesey himself had not fully conceived of what he had created. He was operating on instinct, on the conviction that organised chaos and collective experience could produce something transcendent. That the festival proved him correct came as revelation.

The festival’s impact on the Bay Area music scene proved immediate and structural. Bill Graham had already used the Fillmore Auditorium for Mime Troupe benefit concerts in December 1965 and January 1966, featuring early performances by the Grateful Dead and other local bands. Graham secured a lease on the Fillmore starting in February 1966, beginning his regular programming with shows featuring Jefferson Airplane and other Bay Area acts. The Fillmore became the epicentre of San Francisco’s psychedelic rock scene throughout the late 1960s. Graham’s eye for talent and his understanding of what audiences wanted led to the regular booking of the Grateful Dead, Jefferson Airplane, and Big Brother and the Holding Company, along with scores of other Bay Area acts that might otherwise have remained local phenomena.

The Trips Festival also represented a watershed moment for the Merry Pranksters themselves. LSD would become illegal within nine months, and Kesey faced serious legal jeopardy. He was arrested on marijuana charges in 1966 – twice – and with his legal situation deteriorating, the scene that had grown organically from his Acid Tests began to shift away from Kesey’s direct influence. By Halloween 1966, when the Pranksters threw what they called the “Acid Test Graduation” or “Trip-or-Treat” festival, Kesey announced to his followers that the era of acid consumption was ending and they should now attempt to achieve transcendence through natural means. Kesey would soon fake his suicide, flee to Mexico, be captured, and retreat to his family farm in Pleasant Hill, Oregon, where he would maintain a deliberately secluded life. The Trips Festival became his final major statement of impact on the emerging counterculture.

Yet the legacy of those three days persisted long after Kesey’s departure. The San Francisco scene that crystallised at the Trips Festival became the template for what would evolve into the Summer of Love in 1967. The bands that performed or were first discovered at the festival – the Grateful Dead, Big Brother and the Holding Company (soon to feature Janis Joplin), Jefferson Airplane – became the defining musical voices of the decade. The light show and multimedia approaches pioneered by Owsley Stanley, Ken Babbs, and others at the Trips Festival became standard elements of rock concerts, eventually spreading across the world and profoundly altering how live music was experienced and produced.