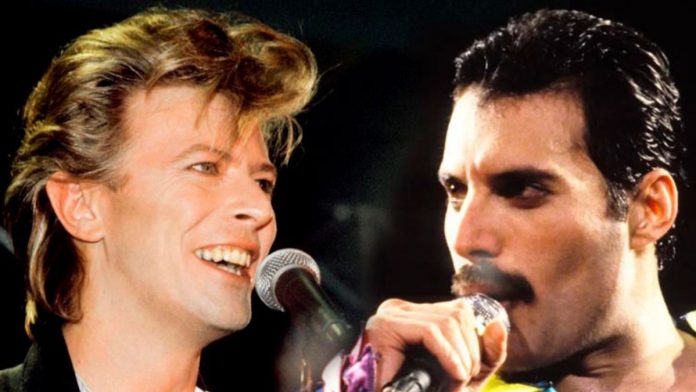

Under Pressure: The Night Queen and David Bowie Created Something Unforgettable

It’s September 1981 in Montreux, Switzerland. Queen are in the middle of recording Hot Space at Mountain Studios, a facility they’d bought a stake in a few years earlier. They’re working on a song called “Feel Like” that isn’t going anywhere. David Bowie happens to be living nearby in Vevey, doing some work on the theme for a forgettable film called Cat People and makes his way to Mountain Studios.

What happens next would become one of the most recognisable moments in rock music history, but nobody planned it that way.

The Accident

Bowie arrives at the studio and Mercury, May, Taylor and Deacon are there. They know each other casually. According to the various accounts that have emerged over the years, what starts as a social visit turns into something else entirely. Bowie agrees to add backing vocals to a Queen track called “Cool Cat.” He records his parts and steps back into the booth to hear what he’s done. He doesn’t like it. The vocals get scrapped.

Instead of leaving, Bowie stays. They start messing around, jamming to old Cream songs, playing whatever comes into their heads. It’s loose and boozy. Then, according to Roger Taylor, someone suggests they might as well write something original. Bowie doesn’t see the point in continuing to cover old material. Why not just create something?

They start building on a riff John Deacon has been developing. There’s some disagreement about who actually wrote the bass line, a piece of it that would become one of the most recognisable in rock history. Deacon says years later that Bowie created it. Bowie says on his website that the line was already written before he arrived. Brian May and Roger Taylor credit Deacon. The truth seems to be that Deacon had been playing with it for a while, perhaps before Bowie showed up. When the band takes a break for pizza and wine, Deacon completely forgets the riff. Taylor remembers it and teaches it back to him when they return.

But something is happening here. The groove is working. May adds a guitar line on top of Deacon’s bass. Bowie isn’t satisfied with the conventional approach. He pushes them to abandon the idea that any of them should prepare what they’re going to do. Instead, Bowie tells each of them to go into the vocal booth one by one and sing the first thing that comes into their heads over the backing track. No planning. No notes written down. Just instinct.

Freddie Mercury does this and what emerges is wordless, scat-sung ad-libs. The de-dahs and the da-does that characterise the song. These were never supposed to be permanent. They were meant to be placeholders, things to replace with proper lyrics later. But nothing they try works as well as what Mercury improvised in that moment, so the scat stays.

The Battle

By the time they have an instrumental track they’re happy with, wine and cocaine have been flowing. Bowie is running between the piano and a 12-string guitar, offering ideas. The energy is strange and electric and also genuinely chaotic. Bowie works with Mercury’s vocal takes, and then he makes a call that shifts everything. He wants to take over the lyrics himself. He wants to control what this song is about.

The band is taken aback. This isn’t how Queen usually works. They’ve built their reputation on Mercury’s writing, on each member contributing ideas. But something about what Bowie is suggesting feels right. They step back. Let him do it.

The song they’ve been calling “People on Streets” gets a new title: “Under Pressure.” The lyrics centre on something real and universal and uncomfortable. This is about the weight modern life puts on you. It’s about anxiety and alienation and the desperate need to connect with someone else. It’s about love as the only answer to pressure.

The vocals they recorded separately. Bowie insisted he and Mercury not hear what the other had sung. They swapped verses blind, which gives the final track its peculiar call-and-response quality. Mercury’s voice is theatrical and huge. Bowie is controlled and almost conversational by comparison. They’re pulling in different directions and that tension is exactly what the song needed.

But even with the song essentially finished, there’s friction. Bowie and Mercury have different ideas about the mix. The track gets finished at the Power Station in New York a couple of weeks later and the mixing becomes another battle. Brian May later admits he wishes Bowie and Mercury could have seen eye to eye on that final step. “It’s a great song,” May said, “but it should have been mixed differently.” The version that was released is a compromise. It’s still brilliant.

The Release

“Under Pressure” comes out on 26 October 1981 as a standalone single. There’s no music video. Both Bowie and Queen are on the road or committed elsewhere. Instead, they piece together stock footage for a video: traffic jams, packed trains, explosions, riots, cars being crushed. The chaos matches what Bowie and Mercury are singing about.

The track hits number one in the UK. It stays there for two weeks. In the United States it reaches number 29, which is still remarkable considering how little airplay it gets. The song appears on Queen’s 1982 album Hot Space even though it was recorded before the album came together. For Bowie, this is his only major release in 1981.

Queen take it on the road immediately. Mercury makes it a centrepiece of their live sets, and the song becomes a fixture in everything Queen does until they stop touring in 1986. Bowie doesn’t perform it live at first. He’s uncomfortable with it in some way, or perhaps he doesn’t think it fits his other material. It isn’t until the Freddie Mercury Tribute Concert in April 1992, more than a year after Mercury’s death from AIDS complications, that Bowie finally sings the song in front of an audience. He does it as a duet with Annie Lennox backed by the surviving members of Queen. It’s extraordinarily moving. After that, Bowie keeps “Under Pressure” in his own catalogue and performs it regularly until his death in 2016.

The Aftermath

Nine years after “Under Pressure” is released, a young rapper called Vanilla Ice samples the bassline for a song called “Ice Ice Baby.” The riff is immediately recognisable. Ice claims he’s done something different with it, added an extra beat, changed it up. Nobody believes him. Eventually legal pressure forces him to acknowledge what he’s done. He pays four million dollars for the rights and Queen and Bowie get songwriting credit on his record. The whole incident winds up damaging Ice’s credibility more than anything else in his career. It becomes the thing he’s defined by.

“Under Pressure” gets covered over the years. My Chemical Romance and The Used do a version. Shawn Mendes records it. Artists keep finding things in the song that matter to them. It appears on countless Queen compilations. Rolling Stone voters name it the second greatest collaboration of all time.

There’s something else too. During those sessions at Mountain Studios, Bowie and Mercury recorded other songs together. Complete tracks. Full arrangements. They were just jamming, trying things out, and they created music that nobody has ever heard. Brian May has acknowledged this. Peter Hince, who was there as Queen’s road crew head, has talked about it. Rock and roll tracks recorded raw but fully formed. But nobody knows exactly who owns them. Do they belong to the Bowie estate or to Queen? The legal complexity has kept them in a vault for over forty years.

“Under Pressure” works because nobody set out to make it. It happened because two brilliant artists found themselves in the same room at the same time in a quiet Swiss town and decided to see what would happen if they trusted their instincts. It happened because 1981 was a different time in rock music. There was still room for spontaneity. There was still room for an evening session to produce something that would last for decades. There was still something dangerous and unpredictable about what two egos in a studio could create.

More than four decades later, “Under Pressure” sounds as immediate as it did in 1981. The lyrics about societal pressure and the need for love feel more urgent now than they did then. Every generation that discovers it finds something that speaks to them. The song endures because Bowie and Mercury made something genuine together, something that came from real tension and real talent and real spontaneity. They made art that doesn’t sound like it was assembled in a committee. It sounds like what it was: two enormous artists colliding at exactly the right moment and creating something neither could have made alone.